An interesting and valuable monograph on St. Mary's Church was written in 1887 by David Ross, a close friend of the Rector, Reverend Frederic French. This not only described many of the interesting features of the church but also included a selection of verses recorded from existing monuments in the churchyard at that time. This has stimulated an interest in recording the inscription verses that can still be seen today.

Monumental inscription verses can inform us of the circumstances by which former residents might have met their demise and provide a pointer to the conditions by which people lived. Gravestones became a feature of churchyards during the early 18th century. Prior to this, prominent members of the community might have been interred in vaults in the chancel of the church whilst the rest of the populace were interred either on the south side of the church or in a small area on the north side (reserved for infant deaths, criminals, the insane and the unfortunates from the Parish Workhouse).

One should remember that superstition or tradition, call it what you will, dictated that the south (sunnier) side of the churchyard was favoured, the north side being the gloomier side, possibly with connotations to the Devil. The north side, being largely free of graves, would be the congregating area for small fairs and social events in medieval times.

Before gravestones, a burial would be marked, if at all, with a wooden cross - a marker that would rot and disintegrate in time. The advent of gravestones allowed the grieving family to record the demise of their relative in situ, as well as in the church register, and in some instances to have a commemorative verse carved. Many of these verses are disappearing due to the effects of weather, pollution and age. An effort has therefore been made to record the remaining examples for posterity. Some of these verses recorded are given below.

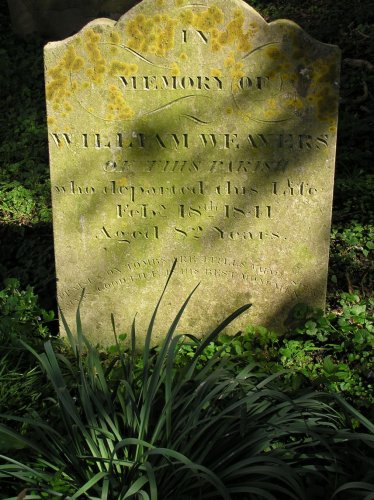

William Weavers (1756-1841)

Praises on tombs are titles vainly spent

A man's good life is his best monument

John Chenery (1788-1817)

I was with sorrow so oppress'd

Which wore my strength away

Which made me wish for Heaven's rest

Which never will decay.

Thomas Ling (1769-1835)

All you that come my stone to see

Pray think upon eternity

Life is uncertain, death is sure,

Sin is the wound and Christ the cure.

Elizabeth Clarke (1727-1777)

Weep no more dear friends let your sorrows cease

My misery is over and I laid down to rest

Though death have got dominion over me

I hope to rise to life and immortality

Ellen Wardley (1849-1862)

Cease here longer to detain me

Fondest mother, drown'd in woe

Now thy kind caresses pain me,

Morn advances, let me go.

John Jessop (1745-1825)

To ringing from his youth, he always took delight,

Now his bell has rung, his soul has took its flight,

We hope to join the choir of heavenly singing,

That far excels the harmony of ringing.

John Farrow (1791-1824)

Long is my rest the shorter was my stay

A youth I was when God took me away

A loving wife I had and parents kind

Likewise two tender babes I left behind

But mourn no more for me dear friends I pray

I hope we all shall meet another day

George Moulton (1798-1832)

When blooming youth and beauty is most brave

Death plucks us up and plants us in the grave

Take care, young folks, precious time to spend

In living, mindful of your latter end.

George Greenard (1745-1830)

Let friends forebear to mourn and weep

While in the dust I sweetly sleep

This frailsome world I left behind

A crown of glory for to find.

Elizabeth Greenard (1756-1822)

Of manners mild to all who knew her dear

The gentlest and kindest of friends lies here

Whose darling wish was comfort to impart

To cheer the drooping soothing aching heart.

James Seaman Jnr (1807-1828)

Here lies a youth whose rising prime

Was all unmark'd by vice or crime

Reader when you, this world, resign

May equal praise be justly thine.

James Seaman (1755-1836)

Farewell, vain world, I've had enough of thee

And now am careless what thou say of me

Your smiles I court not nor your frowns I fear

My cares are past, my head lies quiet here

What faults you have seen in me, take care to shun

And look at home, enough is to be done.

The importance of recording monumental inscriptions was recognised well over a century ago by writers and antiquarians such as Silvester Tissington, who taught at Worlingworth School and wrote "Tissington's Epitaphs". This book was a compilation of the "Monumental Inscriptions of the Most Illustrious Persons of All Ages and Countries", even featuring four former residents of Worlingworth. Published in 1857, the book is quite rare, though the Local History Group has been able to obtain an original.