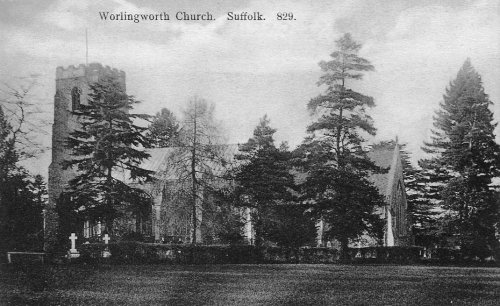

People have worshipped on this spot for possibly a thousand years. The earliest craftsmanship visible in the building today dates back some 700 years and today’s pilgrims may enjoy the work of people from a variety of periods who, in their time, have altered and beautified it and have left their mark on it. This includes tasteful and colourful craftsmanship from our own time, which rightly takes its place alongside the work of past ages.

Church Timeline

1038 The Bishop of Elmham (Aelfric II) gave a third part of the manor and advowson to the Benedictine Abbey at Bury St. Edmunds, indicating that there was a priest here and therefore probably also a church.

1086 The Domesday Survey records that a church existed at Worlingworth at this time. It may well be that this was a building of wood and wattle as there appears to be no Saxon or Norman evidence in the present church.

1280-1310 The present chancel was built. We can date it by looking at the style of the windows which show the early development of the Decorated Style of architecture. In many churches, the chancel is of a different style and date from the other parts because its maintenance was the responsibility of the Rector, who received the Rectorial Tithes (in this case, the monks of Bury St. Edmunds), whilst the parishioners were responsible for the rest of the building.

The 1400s It was during this century that the lofty nave, the western tower and the south porch were built in the Perpendicular Style of architecture. The nave was equipped with its splendid roof, radiant with colour and hovering angels, and beautifully carved benches, of which only two remain, located in the south porch. A magnificent screen, topped by a rood-loft, divided the nave from the chancel, and was surmounted by the great Rood, enabling the congregation to have before them the central fact of the Christian Faith – Christ crucified, with his Mother and St. John at the foot of the cross.

The windows were filled with colourful stained glass, portraying saints, symbols and biblical scenes. Through this craftsmanship and much more, the church was able to provide a kaleidoscope of visual aids to teach the faith to the people, most of whom could not read. The font and its sumptuous cover also date from the 1400s. There is a tradition that these were brought here from the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds, which had a special relationship with the church through its ownership of the advowson of the living. It is however only a tradition and no evidence exists to prove it.

The 1500s The Reformation in the mid 1500s brought great changes to the internal décor of the church. With the services and scriptures in English, it was felt that there was less need for the old visual aids and so a great deal of colour and carving was removed. The great Rood and its loft were taken down, the wall paintings were whitewashed over and the stone altar was dismantled (its top slab became the door step at the south entrance) and was replaced by a wooden table. Side altars and chantry chapels were abolished and the beautiful adornments, metalwork and vestments of the church were sold or disposed of. An old inventory of church goods mentions the following items in use in the church in the early 1500s.

“A lytell Crosse of Sylver, one ‘suit’ of crymsen velvet imbroyderies, one cope of the same sute, one vestment of red velvet, one cope of blake wusted, two copes of sylke, one deken (tunicle, worn by the deacon) of sylke, one hearse cloth, one vestment of wyte sylke, the wayle cloth (the Lenten Veil, which hung during Lent across the chancel in front of the High Altar), two clothes hyng before the candlebeam (also in Lent, in front of the great Rood).”

Following the Dissolution of the Monasteries (including the Abbey at Bury St. Edmunds) in 1538-39, the advowson of Worlingworth was transferred to Anthony Rous of Dennington, who was Lord of the Manor. It is interesting that a member of this ancient family has owned Dennington Hall from Anthony’s time up to the present day.

The 1600s The English Church was beginning to settle into its reformed status during this century. Our parish churches became furnished to cater for the liturgical needs of “The Church of England, by Law Established”, with “plain and Prayer Book” worship, emphasis upon the preaching of the Word, and Communion three times per year.

Worlingworth’s great nave was equipped with new seating to accommodate 400 people in very high-quality workmanship of the period. In the north-east corner of the nave was a box-pew, upon which was carved the date 1630 and the initials ”W.G.”, which may well indicate the person who had made it and whose family had the right to occupy it. Several members of the Godbold family lived in Worlingworth during the 1600s. The Burial Register records burials of “William Godbold the Elder” in 1629, “William Godbold Jnr. Esq.” in 1658 and “William Godbold, Gent.” in 1713. This family were clearly generous to the church; they gave the poor box in 1699, the small collecting shoe in 1622 and also probably had the box pew made. The interior was also equipped with a handsome new pulpit (probably originally a three-decker, with clerk’s desk and reading desk, as at Dennington) and a sturdy Communion Table.

Further destruction of medieval colour and carving took place in 1643 by order of William Dowsing, the Puritan Inspector of Churches for the destruction of “superstitious images and inscriptions”, who visited St. Mary’s on August 27th 1643 and who recorded in his journal,

“Wallingworth, August 27th 1643.

A Stone Cross on the top of the Church.

Three Pictures of Adam on the Porch.

Two Crosses on the Font, and

A Triangle for the Trinity in stone, and

Two other superstitious pictures, and the

Chancel ground to be levelled in 14 days,

Edward Dunstone and John Constable.

William Dod and Robert Bemant,

Churchwardens – 3s 4d”.

It is very likely that, in preparation for this inspection, the people of Worlingworth had (maybe reluctantly) removed as much of the stained glass as they could, painted over the paintings on the screen and taken down some of the angels which adorned the nave roof. It is interesting that nobody appeared to have ordered the total destruction of the font cover. The chancel at this time still had a thatched roof, parts of which were re-thatched in 1674 and 1676. In 1678, the external walls of the chancel were plastered and whitewashed.

1700-1839 This period in the church’s history saw the arrival of John Major at Worlingworth Hall and the emergence of the Henniker family as leading landowners in the parish. John Major and the Henniker family did much to shape the development of the church and parish during this period.

The 1st Baron Henniker had the font cover “restored and beautified” in 1801 and presented the church with an organ, which was opened on 4th September 1796. He also gave himself the power of appointing an organist and duly appointed Miss May Mallett to the position on 24th September of that year. The pipework of that instrument was made entirely of wood. We do not know the identity of its builder but we do know that it cost 5 shillings to transport it here and that Joseph Hart, the village organ builder from Redgrave, was paid 4 guineas for repairing it in 1809.

In 1804, a year after the 1st Baron’s death, the church received a new ring of six bells, paid for by subscriptions collected under the patronage of Elizabeth, Duchess of Chandos (John Major’s younger daughter) and the new Lord and Lady Henniker, the treasurer of the fund being John Jessop, Worlingworth’s redoubtable campanologist.

Preserved in the church is the spit upon which an ox was roasted in 1810 at a great feast organised by the 2nd Baron to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of King George III.

The antiquarian, David Elisha Davy, visited the church in 1808 and his written observations give us some idea of what the building was like at that time. Externally, the chancel walls were still plastered but its thatched roof had by then been replaced by one of tiles. Internally the chancel roof was sealed with plaster. At the east end stood the Communion Table, which was “railed round” on three sides. The areas between the rails and the north and south walls had been made into enclosures; one was used as a vestry and the other contained the parish chest. Over the Communion Table was an altarpiece, with two framed boards inscribed with the Lord’s Prayer, Apostles’ Creed and Ten Commandments.

Davy mentions pieces of medieval glass remaining in the east window and Tom Martin, who visited the church some years earlier, said that there were what he thought to be figures of St. Martin and Thomas a Beckett, also “ three naked figures in a fiery furnace”. In a window on the north side was a figure identified by Davy as St. Philip. In the nave, Davy noted the uniform seating, the pulpit in the south-east angle, also the font, noted as being “at the west end, near the north wall”), with its cover, which then had four of its inscriptions. At the west end was a gallery, upon which the small organ stood, above which, on the wall, hung the Royal Arms of Queen Anne. The base of the rood screen stood (as it does now) in position beneath the chancel arch. Its two sections then formed the western sides of Lord Henniker’s two commodious box-pews in the chancel and fixed to the screen panels were the arms of Henniker and Major.

When Davy paid a return visit to the church in 1839, he noted that these crests “are taken great care of, being covered when there is no service in the church”. To the north of the chancel arch were displayed the colours of the “late Worlingworth Volunteers” which, in 1839, were described as “decaying very fast”. The Volunteers were formed in the late 1790s as a result of the fear in England of a possible war with Napoleon.

1853-1907 This period marked the 54 year incumbency of the Rev’d Frederic French, who arrived as a 30 year old priest, having been curate of Claxton and Hellington in Norfolk and who died here in 1907 aged 83. During his time here, much was done to restore and beautify the church, parts of which were becoming very dilapidated. In 1866, the building was closed for several months whilst the chancel underwent a thorough restoration at a cost in excess of £800, half of which was contributed by the Rev’d French himself. During the removal of the mortar from the ceiling, which held the old chancel roof together, part of the roof crashed towards the east wall. Despite the fact that the Rector and others were standing on parts of the walls at the time, nobody was injured. The Ipswich Journal reported of the work, “In appearance, the chancel is entirely new”. It received a new east wall and east window, four new buttresses, a new oak roof, a floor of encaustic tiles and a hot water apparatus for heating. In the nave the woodwork of the pews was adjusted in order to make them all of a uniform height and the pulpit and reading desk were lowered and altered. The architect was Edward Lushington Blackburne of Bernard Street, London.

A streamer on the church tower “waved in the early morning air” on Wednesday 6th June 1866, the day of the Grand Re-Opening by the Bishop of Norwich (in whose Diocese Worlingworth then was), who also confirmed 62 females and 32 males from Worlingworth, Southolt and neighbouring parishes.

In 1867, the old western gallery was taken down revealing the tower arch and the organ was placed on the north side of the chancel. This in turn was moved to the Old School-Room (at the east end of the churchyard) in 1872, when a new two-manual and pedal instrument, with 11 speaking stops, made by Stidolph of Woodbridge, was erected on the north side of the nave. The gallery was taken down by the celebrated carpenter and wheelwright James Newson, who lived in the Wheelwright’s cottage opposite the church for over 50 years.

On Easter Sunday 1871, the memorial window to John, 4th Baron Henniker, in the base of the western tower was dedicated. This window, by Clayton and Bell, was the gift of his tenants and other Worlingworth parishioners.

Whit Monday 1893 saw the re-dedication of the restored font cover. The preacher was Canon J.J. Raven of Fressingfield and the service was followed by tea in the Rectory gardens. The work of conservation was carried out by Mr Robert Morris of Ditchingham, under the careful direction of Augustus Frere, Architect, of London. Mr. Frere, who restored the churches of Horham and Haughley, had reported that “restoration” of the font cover would in fact be “destruction”, but it was “preservation” which was required. The cover was therefore taken apart, stage by stage, examined and carefully reconstructed, also equipped with a balance and weights. The work cost £115 5s.

After only 27 years of service, the Stidolph organ was judged to have “failed to give satisfaction” and was replaced by a two-manual and pedal organ with 7 speaking stops by Norman Bros. and Beard. The organ was funded by a subscription list initiated by the Rector and contributed to by his extensive family and friends and many leading parishioners in the village. Sir Frederick Bridge (Organist of Westminster Abbey), who often stayed at Hoxne, selected the new instrument and it was he who opened it with a recital at its dedication on St. Cecilia’s Day in 1899 by the Bishop of Norwich. The service was attended by all the clergy and churchwardens of the Hoxne Deanery. The clergy progressed from the Rectory to the church in procession with 100 school children. This was indeed a special day as it was also the Rector’s 76th birthday.

In 1901, the Rector and his family provided the stone reredos behind the High Altar, designed and made by G.E. Hawes, Church Furnishers, of Duke’s Place, Norwich. The reredos was dedicated to the memory of the Rector’s wife, Anna Maria French, who died suddenly in April that year.

A great era in the parish's history came to an end in October 1907 with the death of the Reverend Frederic French at the age of 83. An account of his funeral, written in the Framlingham Weekly News at the time, captures the sadness of the occasion but nevertheless describes the lasting legacy and humane qualities possessed by a true servant of God and friend of the common man.